I remember Ash Wednesday like it was yesterday. The 16th of February 1983. It was my grandmother’s 67th birthday. I rode my bike to school that day so when Mum walked into my year 6 classroom to collect me, I knew something must be wrong. Within twelve hours, more than 180 fires fanned by gale force winds had left a path of destruction spanning from South Australia where I grew up, right through to Victoria. Years of severe drought and extreme weather combined to create one of Australia’s worst fire days in a century. There were 28 deaths in South Australia that day, and 47 in Victoria, including 14 CFA and 3 CFS volunteer fire-fighters.

The fire was extinguished before it reached our town, but as a young child it scarred me. “It” wasn’t just one day, but years punctuated by death and destruction and recovery. Entire towns had been wiped out and swathes of farmland razed, left desolate of life. My Dad worked for months afterwards, cutting down the burnt pine forests, only returning home every few days literally black with caked-on soot. The impact of the fires was inescapable.

And so I’ve spent a lifetime terrified, and somewhat obsessed, by bushfires.

After the Black Saturday fires, I took on a worker at our farm whose wife and two young sons died on that horrendous day. They had a bushfire survival plan, but when fireballs grew taller than skyscrapers upon the horizon, they realised it wouldn’t be safe to stay. Rod ran out to the shed to fetch the car but by the time he got back the house, they were gone. 173 lives were lost that day.

Bushfires are ferocious and awful and cruel, and in our rugged Australian landscape they are as inevitable as drought and flood. As I write this, our farm in the NSW Southern Highlands sits at the epicentre of three separate fire fronts. Of course, I’m hoping they won’t reach us. Or at least will travel slowly enough to allow livestock and wildlife to retreat, and firebreaks around buildings to be effective. But for now, all I can do is follow my fire plan and the advice of our local Rural Fire Service, who are doing a superb job of keeping us informed and safe. Not just this week or this month, but all year round.

It’s a stressful and frightening and exhausting time. Many of the towns where lives and homes have been lost are very familiar to me. But what makes it even harder is the opinion being sprouted in the media and online by every man and his dog, all playing the blame game and making demands about what should be done. Even though most of them have no flaming idea of the complexities at play.

They’re so sure that they’re right, it doesn’t enter their consciousness to consider an alternate point of view. And why is that? Because ignorance cannot recognise itself.

Of course, it’s not just about the fires. All around us, across all facets of life, we see examples every day of people who simply do not possess the skills needed to recognise their own incompetence or lack of knowledge. They’re ignorant, but they don’t know what they don’t know.

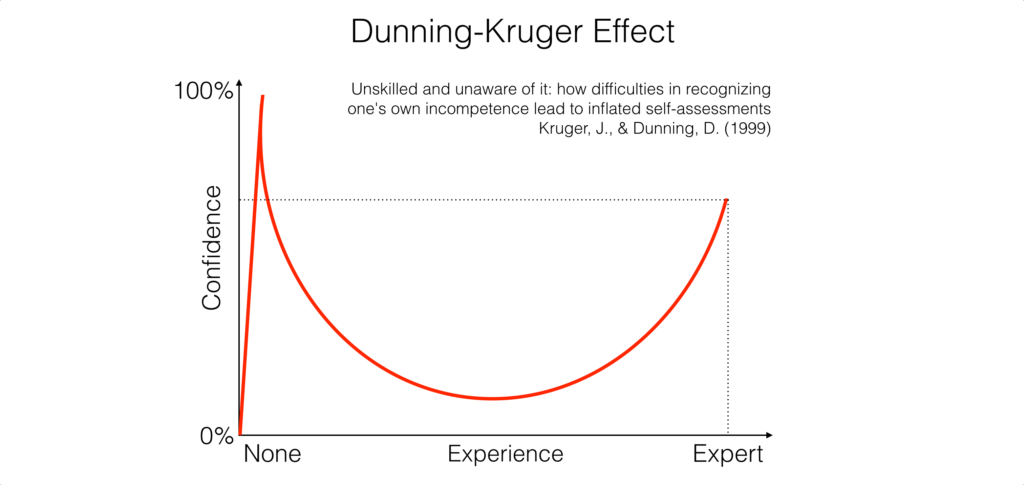

This form of cognitive bias has a name: the Dunning-Kruger Effect. What psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger identified in their research is that people who are less competent consistently over-rate their abilities while – paradoxically – those with higher levels of expertise tend to under-rate them.

And, as the level of knowledge and capability increases from zero up, the level of confidence will actually drop as the individual begins to appreciate just how much they have to learn; and only rebuild as a level of expertise is attained.

In other words, the less we know, the more confident we are; and the more we learn, the more we realise there is to learn.

The RFS and Fire and Rescue – along with all our emergency services and first responders right across Australia’s fire affected areas – have done a sterling job. It’s not over yet, but when you consider the loss of life this summer as compared with other catastrophic bushfires, it’s really quite remarkable. And this has much to do with what we’ve learned from past disasters, from the emergency services and systems that have been put in place, and from the expertise that has been developed across our agencies to plan for and manage our fire seasons, which are increasing in intensity.

So, if you have time on your hands and feel compelled to offer advice about the current bushfire disaster, can I suggest that you stop and think twice. It might be that you don’t know what you don’t know, and perhaps a simple “thank you” to our frontline may be more appropriate.

Leave a Reply